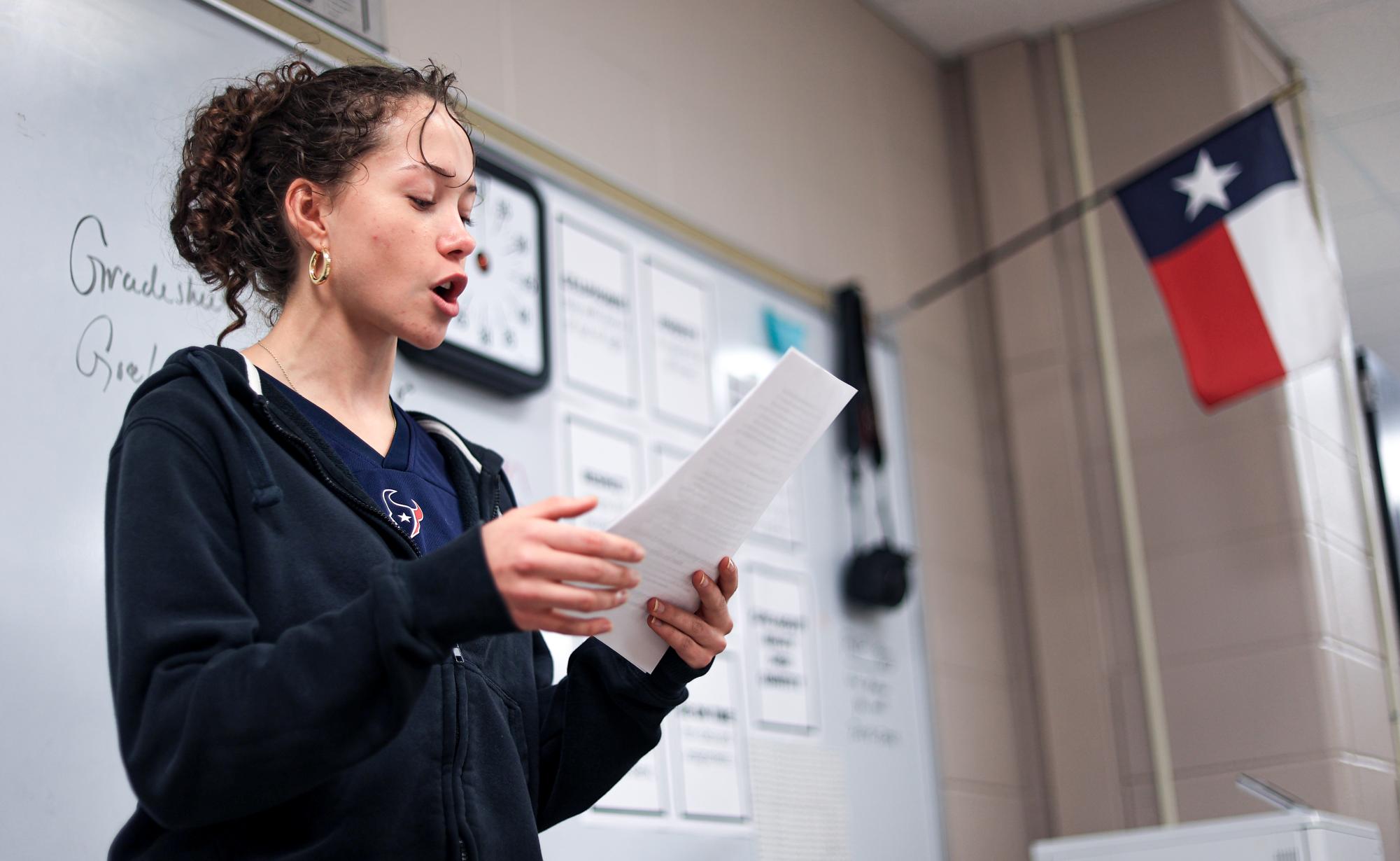

Sophomore Ava Aldridge’s heels clicked down the dark stairwell leading to the basement of the Marrs McLean Science building at Baylor University. The feeling of anxiety-induced nausea mixed with the paced walk there, meant her face was flushed before the round even began.

Whether or not it looked like it though, Aldridge was dead confident. Lincoln-Douglas debate was her turf, and Fiona Fox from Magnolia West High School was her prey. She refused to walk back up those stairs anything less than region 2-6A champion.

“It didn’t feel real, honestly,” Aldridge said. “Not like in the ‘Oh, I could have never gotten this,’ sense, but I just think it was just so picture perfect. It was like, movie and everything.”

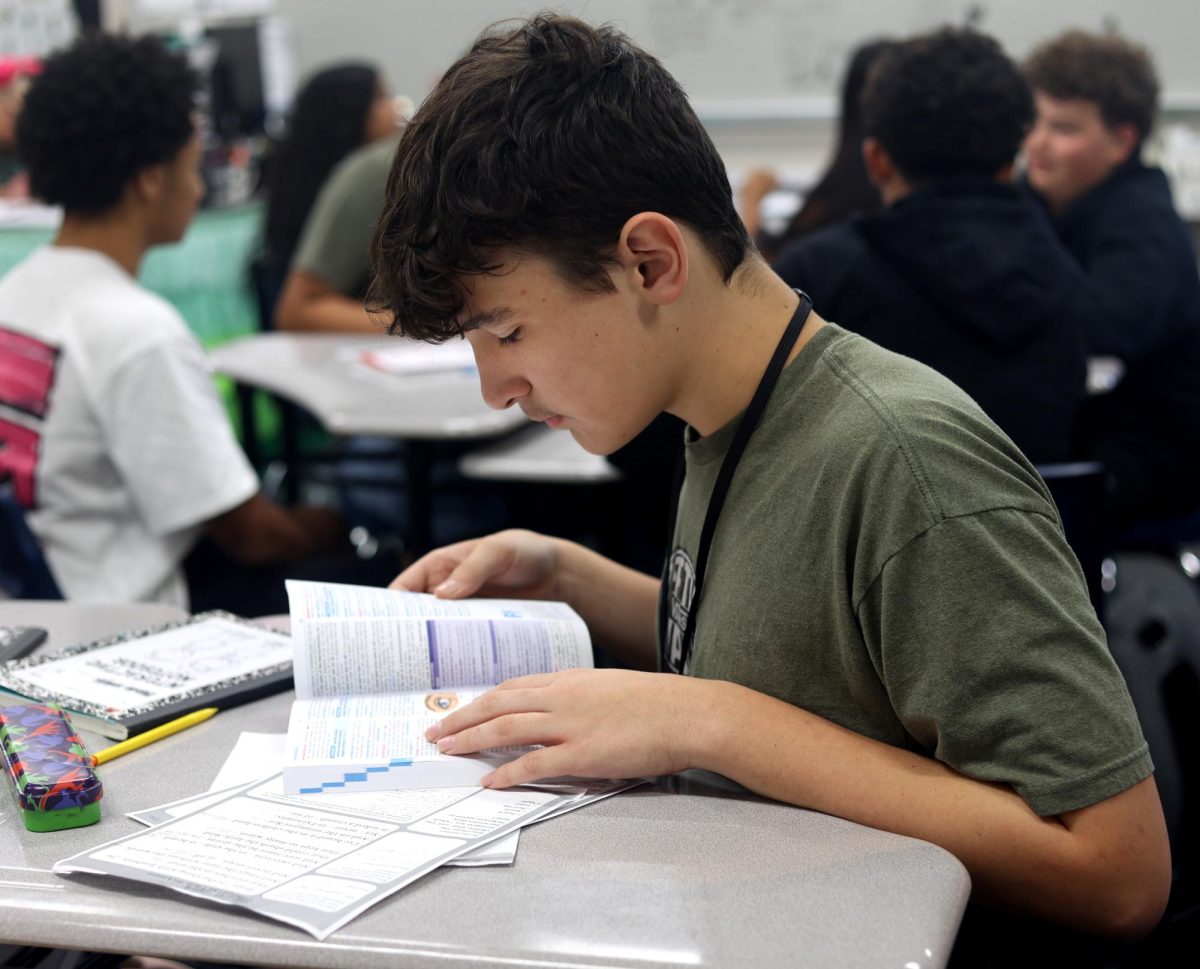

Aldridge grew up speaking out for others; whether it was calling out discrimination or drawing pride-ally flags on her dirty converse, using her voice came naturally. Despite her constant applications, those skills never reached the Moorhead Junior High debate club on claims of being too full.

Her freshman year however, she entered the Debate I class with coach Joseph Collatos and consequently UIL debate too. Collatos said while Aldridge’s skills were unrefined, her passion stood out.

“It was obvious how smart she was and excited to get into new things,” Collatos said. “Which I think really helped her get to where she is now. (New debaters often) freak themselves out, which is something she kind of experienced last year. But she’s found a way to manage it this year though and that’s been key in her success.”

At an invitational in November of 2023, which was one of her first, Aldridge was arguing in favor of the use of artificial intelligence in media arts. Although composed outwardly, she could feel the anxiety consuming her as every second passed.

“I thought for sure I was losing so badly, this guy I was debating was more experienced than me, weather than me and he was older,” Aldridge said. “It felt like everything he said just stuck. When I got into the hallway after round, I just sobbed. What I didn’t know at the time was that you can’t ever predict a round.”

Aldridge won that round, albeit just barely. Either way, the round put a spotlight on her uncontrollable anxiety; the kind of anxiety she describes as a gaping hole in her chest.

“It’s just like if somebody was constantly in your ear, telling you that you’re not going to do well,” Aldridge said. “No matter how much I tried to box breathe or you know breathe deep, it really just went away whenever it wanted to. It wasn’t something I could control.”

That pit was deep enough to hold her back from advancing past preliminary rounds at district last year.

“(The district meet) did not leave me with a good aftertaste,” Aldridge said. “Coming into this year, I felt like a failure. I felt like my last tournament that I did last year, that was actually high stakes – I threw it. It didn’t feel like I was gonna do good this year at all.”

Overcoming

Against her self-proclaimed odds, Aldridge’s medal collection grew with every meet. For each tournament she competed, the anxiety shedded away. She started to take control.

“It was gradual, but I feel like the realization hit at district,” Aldridge said, adding it was the first time she’d broken past semi-finals. “I actually was improving, and so was my confidence. Me finally moving up to the next level was so refreshing, and it especially made me feel accomplished.”

Aldridge advanced to finals, but lost the gold medal to Reana Mohler from The Woodlands High School. However, placing second still qualified her for region, scheduled for April 26-27.

“Going into the region, you know, the pit wasn’t there,” Aldridge said. “Nervousness: yes, but it was different than before. I think I was just very fueled to win, more than ever at region.”

This year’s topic was “Standardized testing is detrimental to equity in K-12 education.”; Round one, Aldridge was neg. According to her, she “wasn’t selling it enough,” that round, but the judge disagreed.

After winning her first round and approaching the second, she felt an unexplainable surge of confidence that carried her through the rest of the tournament.

“Don’t know how, but (the confidence) came randomly,’ Aldridge said. “I read the initial constructive well, I answered CX (cross examination) questions properly, you could just tell that I knew what I was talking about. The best part; my opponent just dropped my case.”

Out of the first six rounds, Aldridge went undefeated, leaving just the final round. By then she was already qualified for state, now was just a dash for the gold medal. And discovering her opponent was Fiona Fox from Magnolia West made that gold seem shinier.

Showdown

Aldridge debated Fox two months earlier at the Caney Creek Invitational on March 1–the last invitational before district – at which Fox ravaged Aldridge and her team’s arguments. But the thought of defeat on Fox’s face fueled Aldridge to go beyond.

“I was like, ‘this is like redemption heaven,’ I need to do this,” Aldridge said. “And I felt really good too. But just before I went into the round, Collatos warned me that they were going to try and use an intimidation tactic.”

Fox invited anyone she could to spectate: Her team, coaches, family, even friend’s family members she’d never met. Every time Aldridge spoke, all the spectators glared, but when Fox spoke they turned their backs as per her request.

LD debate is a public event, meaning Aldridge had to endure. To avoid the crowd staring her down she tunneled her vision onto one judge after every case, and it worked.

“I think seeing them there made me want to win even more,” Aldridge said. “Like ‘You really think this is going to work on me? Do you really need an intimidation tactic to even rig your chances of success against me? No,’ I was tired of her beating me, so I wasn’t going to let it happen.”

Aldridge left the round exhausted. At the award ceremony, she was so drained that she hardly noticed everyone lined up to hear the placements.

As they listed the names, she bowed her head and prayed.

“I was like, ‘Please, please, let them call her for second place,’” Aldridge said. “And then I heard her name, and it felt unreal watching her go up before me, knowing I was next. I just kind of started swaying and shuffling up towards the man who’s giving off the award. And it just didn’t feel real.”

Aldridge stood silent, gold medal in hand, only snapping to reality after Collatos began celebrating.

“I’m emotional, I can cry, but for some reason, no tears would come out,” Aldridge said. “I don’t know why. So I was just giggling laughing the entire time; Swirling in circles and kind of almost like in a dizzy spell.”

Aldridge described the moment as a haze, but remembers calling her teammates and mother in celebration.

The Fight Continues

Advancing to state places Aldridge of the top 12 LD debaters in Texas 6-A. She’s the second debater to be named region champion from the school in three years, first being senior Breshad Robinson. She intends to extend the title to State on May 19-20 at the University of Texas in Austin, where she will again compete with Fox and bronze medalist Jordan Lister from Waxahachie High School.

“To have the ability to go toe-to-toe with experienced debaters on a topic like this in a style like LD takes a ton of mental fortitude,” LD debate coach Stephen Green said. “As a freshman, we all saw she had this level of potential but fear and anxiety was getting in the way. Now that Ava figured out how to move past being her own biggest threat, everybody else better watch out.”